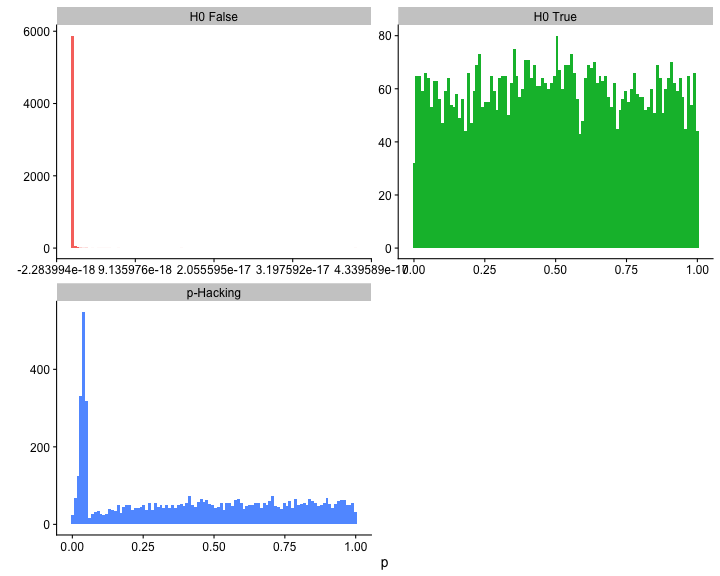

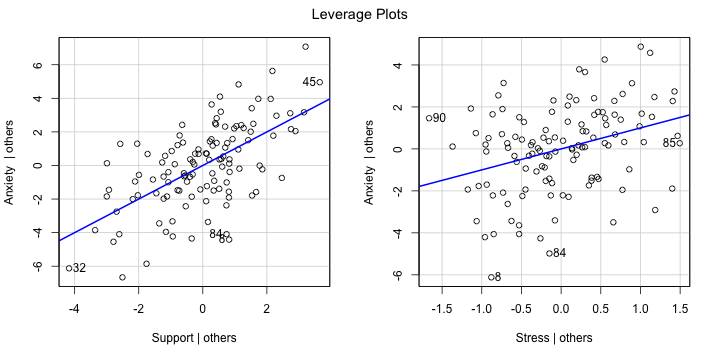

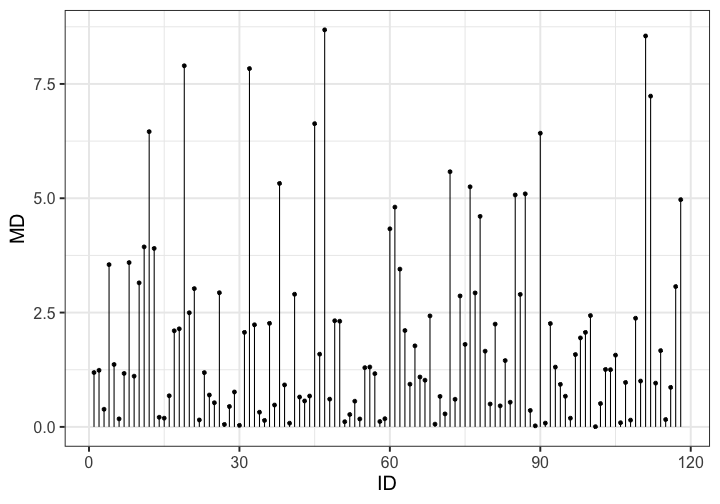

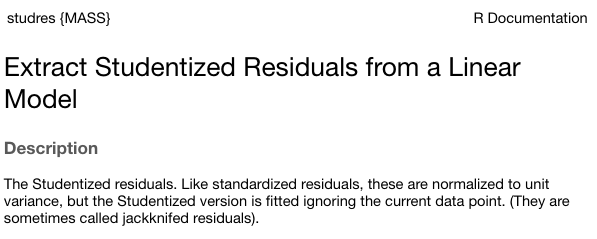

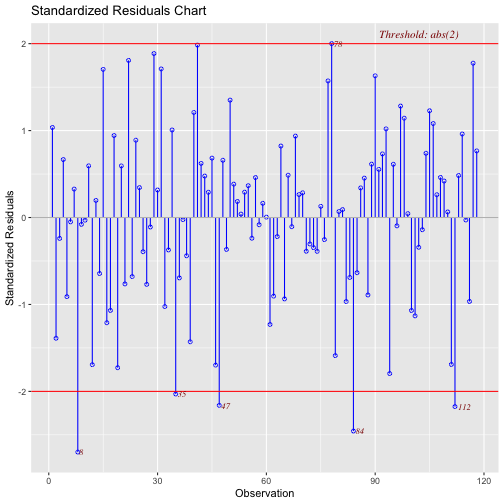

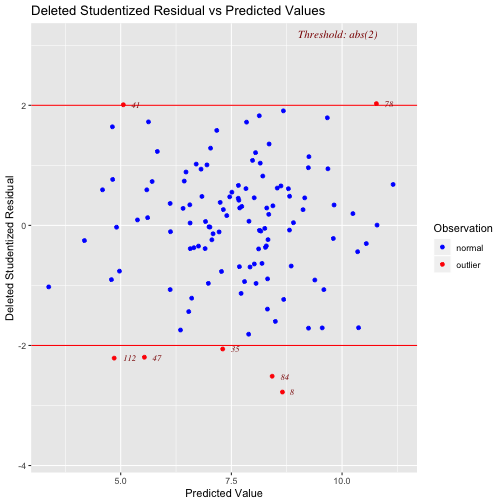

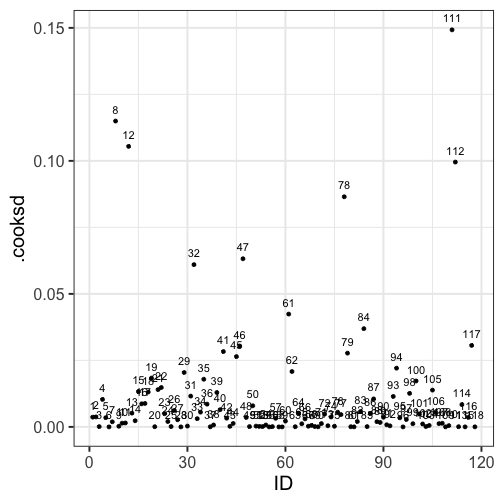

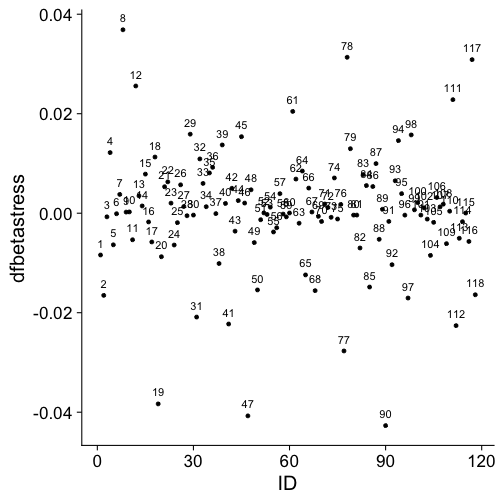

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Assumptions and Diagnostics II --- ## Last time Assumptions and diagnostics Evaluate measurement error with reliability statistics `\((\alpha, \omega, \text{ Inter-rater, test-retest})\)` Use residuals to confirm whether you - correctly specified the form of your model - included the correct variables - have homoscedasticity - have independence among errors - have normally distributed errors Thoughts on Lynam et al. (2006)? --- ## Today - Researcher degrees of freedom - Screening data - Outliers - Multicollinearity --- In addition to the assumptions of models that we discussed last class, there's also an underlying assumption* that our models are developed independent of the data. One easy way to violate this assumption is to change your regression model based on either the significance test(s) of the model or the fit. - Changing the model based on assumptions does violate the data-model-independence assumption, but it's unclear how this affects the inferences. In general, it's a good idea to validate the new model using a new dataset. - Changing the model based on the significance tests is *bad* and it's fairly clear how this affects our inferences. What do you expect the distribution of `\(p\)`-values to look like when the null is true and when the null is false? .small[`*` this is true for all statistical tests] --- <!-- --> --- ## Screening your data ### Steps for screening 1) Calculate univariate and bivariate descriptive stats + Check the min and max to make sure data were entered correctly + Check the class of the variable + is your grouping variable a factor or numeric? + Check for skew or compare the mean and median + Compare correlation matrices with pairwise and listwise deletion for bias in missingness. + Calculate reliability for your scales. --- ## Screening your data ### Steps for screening 2) Plot univariate and bivariate distributions + Look for skew and outliers + Check correlation heat maps for expected and unexpected patterns in items --- ## Screening your data ### Steps for screening 3) Test the assumptions of your regression model(s) + Calculate the variance inflation factor of each term (if you have two or more) to help check for correctly specified models. + Graph residuals by predictors to check for endogeniety. + Graph residuals by fitted values to check for homoscedasticity. + Graph residuals by ID number (or date, or another variable not in your model) to check for independence. + Graph the distribution of residuals or the Q-Q plot to check for normality. --- ## Screening your data ### Steps for screening 4) Look for univariate or multivariate outliers. --- ## Outliers - Broadly defined as atypical or highly influential data point(s) - Due to contamination (e.g. recording error) or accurate observation of a rare case - Univariate vs. Multivariate How do we typically describe or identify outliers? ??? Focus on influential part -- what do we mean by influential? How do we see the influence of outliers in the case of estimating the mean? --- ## Outliers Outliers can be described in terms of three different metrics. Each metric conveys a sense of the magnitude of outliery-ness the case exhibits. However, some metrics also describe the degree to which your inferences will change: 1. Leverage + How unusual is this case from the rest of the cases in terms of predictors? 2. Distance + How distant is the observed case from the predicted value? 3. Influence + How much the does regression coefficient change if case were removed? --- ## Outliers ### Leverage **Leverage** tells us how far observed values for a case are from mean values on the set of IVs (centroid). - Not dependent on Y values - High leverage cases have greater potential to influence regression results --- ### Example Recall our example from the previous lecture: ```r model.1 <- lm(Anxiety ~ Support, a_data) aug_1<- augment(model.1) model.2 <- lm(Anxiety ~ Support + Stress, a_data) aug_2<- augment(model.2) ``` --- ## Outliers ### Leverage ```r library(car) leveragePlots(model.2) ``` <!-- --> --- ## Outliers ### Leverage One common metric for describing leverage is **Mahalanobis Distance**, which is the multidimensional extension of Euclidean distance where vectors are non-orthogonal. Given a set of variables, `\(\mathbf{X}\)` with means `\(\mathbf{\mu}\)` and covariance `\(\Sigma\)`: `$$\large D^2 = (x - \mu)' \Sigma^{-1} (x - \mu)$$` --- ## Outliers ### Leverage ```r (m = colMeans(a_data[c("Stress", "Support")], na.rm = T)) ``` ``` ## Stress Support ## 5.180003 8.730000 ``` ```r (cov = cov(a_data[c("Stress", "Support")])) ``` ``` ## Stress Support ## Stress 3.520270 3.223006 ## Support 3.223006 10.741122 ``` ```r (MD = mahalanobis(x = a_data[,c("Stress", "Support")], center = m, cov = cov)) ``` ``` ## [1] 1.188998950 1.237358897 0.385394451 3.548375033 1.364788762 0.175924047 ## [7] 1.169425691 3.593815125 1.108646512 3.150340743 3.936659820 6.456398132 ## [13] 3.903288913 0.210639676 0.190129552 0.680759396 2.101979146 2.145263771 ## [19] 7.897617677 2.496357970 3.024204941 0.152359531 1.187253882 0.697581144 ## [25] 0.528541330 2.934348088 0.054136643 0.446176891 0.763828757 0.034051187 ## [31] 2.068091370 7.835913540 2.233415324 0.320719554 0.141581776 2.265144764 ## [37] 0.478286624 5.324471355 0.918681013 0.080714850 2.900649779 0.653213992 ## [43] 0.567668929 0.674874227 6.631156703 1.590097500 8.683363557 0.606691853 ## [49] 2.321371815 2.310769549 0.113451052 0.270527370 0.561709786 0.173923755 ## [55] 1.295318406 1.309637556 1.164659827 0.117939937 0.179150339 4.332234641 ## [61] 4.806527636 3.450396009 2.107755635 0.933552335 1.772730756 1.090801040 ## [67] 1.020685220 2.427673952 0.060039225 0.667349141 0.284680081 5.580185237 ## [73] 0.603932146 2.863874060 1.804850098 5.250856454 2.930189802 4.604538128 ## [79] 1.655738461 0.500137386 2.247072239 0.460429051 1.450763036 0.539196443 ## [85] 5.071650028 2.897537184 5.097062163 0.360061040 0.023852326 6.421928251 ## [91] 0.082494581 2.260026971 1.307449811 0.930555331 0.670248486 0.190014647 ## [97] 1.582269376 1.946790663 2.067230016 2.434637951 0.004787446 0.510430814 ## [103] 1.256167606 1.250923478 1.568773151 0.091447039 0.972136982 0.147803353 ## [109] 2.375993824 1.002608629 8.549542234 7.232965656 0.956679521 1.667979791 ## [115] 0.161125775 0.864550505 3.069120158 4.969126241 ``` --- <!-- --> --- ## Outliers ### Distance - **Distance** is the distance from prediction, or how far a case's observed value is from its predicted value * i.e., residual * In units of Y. What might be problematic at looking at residuals in order to identify outliers? ??? Problem: outliers influence the regression line, won't be easy to spot them --- ## Outliers ### Distance - Raw residuals come from a model that is influenced by the outliers, making it harder to detect the outliers in the first place. To avoid this issue, it is advisable to examine the **deleted residuals.** - This value represents the distance between the observed value from a predicted value _that is calculated from a regression model based on all data except the case at hand_ - The leave-one-out procedure is often referred to as a "jack-knife" procedure. --- ### Distance Other residuals are available: * **Standardized residuals**: takes raw residuals and puts them in a standardized unit -- this can be easier for determining cut-offs. `$$\large z_e = \frac{e_i}{\sqrt{MSE}}$$` --- ### Distance Other residuals are available: * **Studentized residuals**: The MSE is only an estimate of error and, especially with small samples, may be off from the population value of error by a lot. Just like we use a *t*-distribution to adjust our estimate of the standard error (of the mean) when we have a small sample, we can adjust out precision of the standard error (of the regression equation). `$$\large r_i = \frac{e_i}{\sqrt{MSE}(1-h_i)}$$` where `\(h_i\)` is the ith element on the diagonal of the hat matrix, `\(\mathbf{H} = \mathbf{X}(\mathbf{X'X})^{-1}\mathbf{X}'\)`. As N gets larger, the difference between studentized and standardized residuals will get smaller. --- ### Distance **Warning:** Some textbooks (and R packages) will use terms like "standardized" and "studentized" to refer to deleted residuals that have been put in standardization units; other books and packages will not. Sometimes they switch the terms and definitions around. The text should tell you what it does. ```r ?MASS::studres ```  --- ```r library(olsrr) ols_plot_resid_stand(model.2) ``` <!-- --> --- ```r ols_plot_resid_stud_fit(model.2) ``` <!-- --> --- ## Outliers ### Influence **Influence** refers to how much a regression equation would change if the extreme case (outlier) is removed. - Influence = Leverage X Distance Like distance, there are several metrics by which you might assess any case's leverage. The most common are: - Cook's Distance (change in model fit) - DFFITS (change in model fit, standardized) - DFBETAS (change in coefficient estimate) --- ## Outliers ### Influence **Cook’s Distance** is calculated by removing the ith data point from the model and recalculating the regression. It summarizes how much all the values in the regression model change when the ith observation is removed. `$$CD_i = \frac{\sum_{j=1}^n(\hat{Y}_j-\hat{Y}_{j(1)})^2}{(p+1)MSE}$$` --- ### Cook's Distance <!-- --> --- ## Outliers ### Influence **DFFITS** indexes how much the predicted value for a case changes if you remove the case from the equation. **DFBETAs** index how much the estimate for a coefficient changes if you remove a case from the equation. ```r head(dffits(model.2)) ``` ``` ## 1 2 3 4 5 6 ## 0.142822222 -0.194364090 -0.026149990 0.133725184 -0.130437196 -0.004986982 ``` ```r head(dfbeta(model.2)) ``` ``` ## (Intercept) Support Stress ## 1 0.076047188 -0.0017168702 -0.0083977784 ## 2 0.022146938 0.0045635001 -0.0165118777 ## 3 0.003825565 -0.0004751821 -0.0007221716 ## 4 -0.045340834 -0.0007265234 0.0121830652 ## 5 -0.039420102 0.0065137198 -0.0063488839 ## 6 -0.001418211 0.0001272720 -0.0001032229 ``` --- <!-- --> --- ## Outliers 1. Leverage + How unusual is this case from the rest of the cases in terms of predictors? 2. Distance + How distant is the observed case from the predicted value? 3. Influence + How much the does regression coefficient change if case were removed? Consider each of these metrics in the context of research degrees of freedom. Do some of these metrics change the independence of successive inferential tests? How might this be problematic for Type I error? What can you do to ensure your analysis is robust? --- ## Recommendations - Analyze data with/without outliers and see how results change - If you throw out cases you must believe it is not representative of population of interest or have appropriate explanation - Don't throw out data just to be "safe". Data are hard to collect and outliers are expected! --- ## Multicollinearity **Multicollinearity** occurs when predictor variables are highly related to each other. - This can be a simple relationship, such as when X1 is strongly correlated with X2. This is easy to recognize, interpret, and correct for. - Sometimes multicollinearity is difficult to detect, such as when X1 is not strongly correlated with X2, X3, or X4, but the combination of the latter three is a strong predictor of X1. --- ### Multicollinearity Multicollinearity increases the standard errors of your slope coefficients. `$$\large se_{b} = \frac{s_{Y}}{s_{X}}\sqrt{\frac {1-R_{Y\hat{Y}}^2}{n-p-1}}\sqrt{\frac{1}{1-R_{12}^2}}$$` - Perfect collinearity never happens. Like everything in statistics (except rejecting the null), it's never a binary situation; there are degrees of multicollinearity. More multicollinearity = more problematic model. --- ## Multicollinearity ### Diagnosis Multicollinearity can be diagnosed with tolerance. Tolerance: `\(1-R_{12}^2\)` - Also look for models in which the coefficient of determination is large and the model is significant but the slope coefficients are small and non-significant. - Look for unstable slope coefficients (i.e., large standard errors) - Look for sign changes --- ## Multicollinearity ### Ways to address * Increase sample size - Remember, with small samples, our estimates can be wildly off. Even if the true relationship between X1 and X2 is small, the sample correlation might be high because of random error. * Remove a variable from your model. * Composite or factor scores - If variables are highly correlated because they index the same underlying construct, why not just use them to create a more precise measure of that construct? * Centering - This is especially important if your model includes interaction terms. --- ## Suppression Multicollinearity is related to suppression. Normally our standardized partial regression coefficients fall between 0 and `\(r_{Y1}\)`. However, it is possible for `\(b_{Y1}\)` to be larger than `\(r_{Y1}\)`. We refer to this phenomenon as **suppression.** * A non-significant `\(r_{Y1}\)` can become a significant `\(b_{Y1}\)` when additional variables are added to the model. * A *positive* `\(r_{Y1}\)` can become a *negative* and significant `\(b_{Y1}\)`. --- ## Suppression Recall that the partial regression coefficient is calculated: `$$\large b^*_{Y1.2}=\frac{r_{Y1}-r_{Y2}r_{12}}{1-r^2_{12}}$$` -- Is suppression meaningful? ??? Imagine a scenario when X2 and Y are uncorrelated and X2 is correlated with X1. (Draw Venn diagram of this) Second part of numerator becomes 0 Bottom part gets smaller Bigger value --- class: inverse ## Next time... Causal models