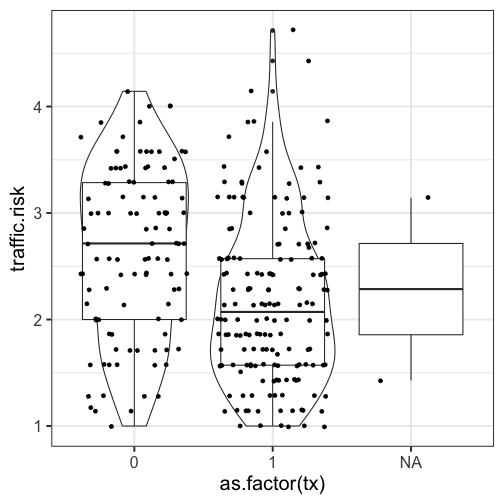

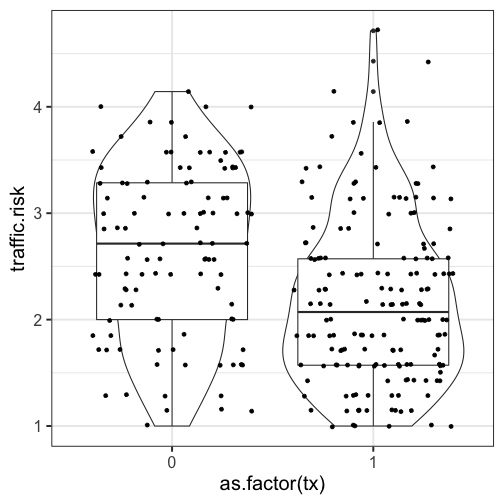

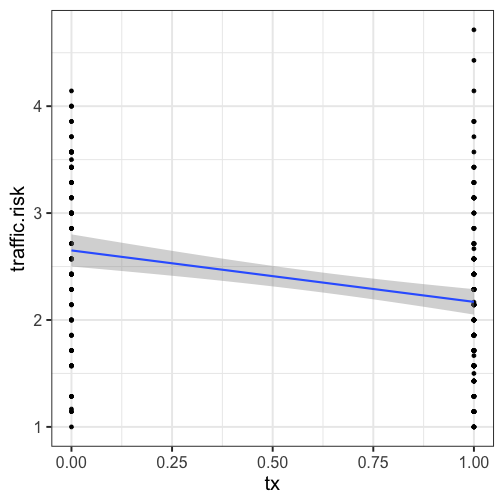

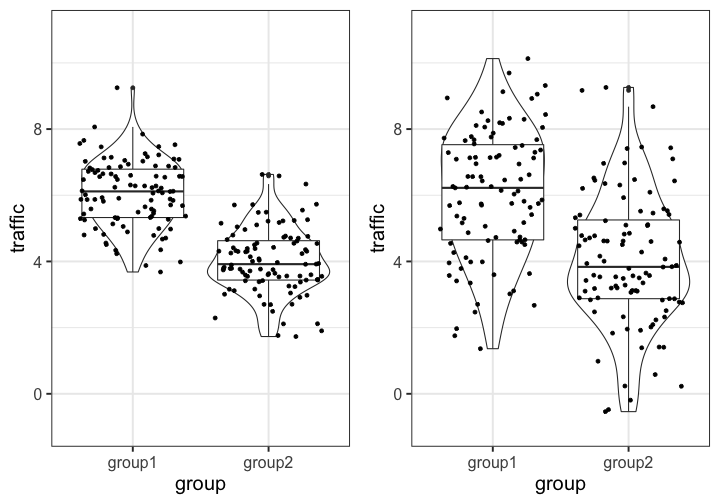

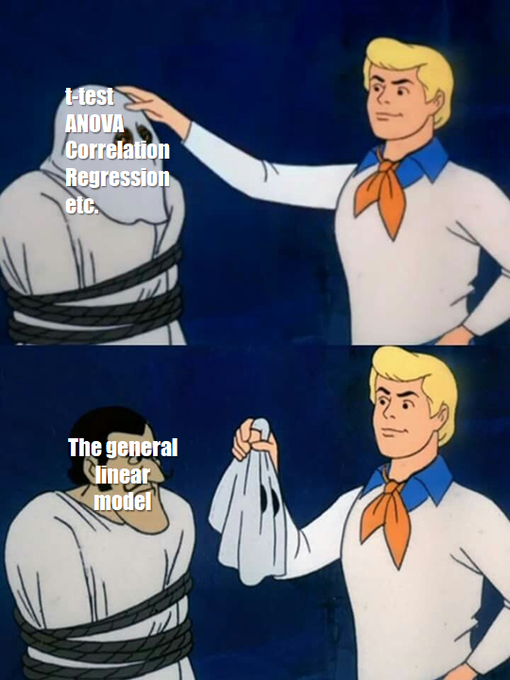

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # General Linear Model --- ## Last time Wrap up univariate regression - Confidence and prediction bands - Matrix algebra - Model comparison --- ## Today General linear model --- ## Models - Thus far you have used t-tests, correlations, and regressions to test basic questions about the world. - These types of tests can be thought of as a model for how you think "the world works" - Our DV (Y) is what we are trying to understand - We hypothesize it has some relationship with your IV(s) (Xs) `$$Y = X + E$$` --- .pull-left[ ### Independent samples t-test ```r t.1 <- t.test(y ~ x, data = d) ``` - Y is continuous - X is a categorical/nominal (dichotomous) factor ] .pull-left[ ### Univariate regression ```r r.1 <- lm(y ~ x, data = d) ``` - Y is continuous - X is continuous ] --- ## General linear model This model (equation) can be very simple as in a treatment/control experiment. It can be very complex in terms of trying to understand something like academic achievement The majority of our models fall under the umbrella of a general(ized) linear model + The **general linear model** is a family of models that assume the relationship between your DV and IV(s) is linear and additive, and that your outcome is normally distributed. + This is a subset of the **generalized linear model** which allows for non-linear associations and non-normally distributed outcomes. All models imply our theory about how the data are generated (i.e., how the world works) --- ## Example ```r psych::describe(traffic, fast = T) ``` ``` ## vars n mean sd min max range se ## id 1 280 140.50 80.97 1 280.00 279.00 4.84 ## tx 2 274 0.62 0.49 0 1.00 1.00 0.03 ## traffic.risk 3 272 2.35 0.81 1 4.71 3.71 0.05 ``` --- ```r ggplot(traffic) + aes(x = as.factor(tx), y = traffic.risk) + geom_violin() + geom_boxplot() + geom_jitter() + theme_bw(base_size = 20) ``` <!-- --> --- ## example ```r t.1 <- t.test(traffic.risk ~ tx, data = traffic, var.equal = TRUE) t.1 ``` ``` ## ## Two Sample t-test ## ## data: traffic.risk by tx ## t = 4.9394, df = 268, p-value = 1.381e-06 ## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0 ## 95 percent confidence interval: ## 0.2893360 0.6728755 ## sample estimates: ## mean in group 0 mean in group 1 ## 2.650641 2.169535 ``` --- ## example ```r r.1 <- cor.test(~ traffic.risk + tx, data = traffic) r.1 ``` ``` ## ## Pearson's product-moment correlation ## ## data: traffic.risk and tx ## t = -4.9394, df = 268, p-value = 1.381e-06 ## alternative hypothesis: true correlation is not equal to 0 ## 95 percent confidence interval: ## -0.3946279 -0.1755371 ## sample estimates: ## cor ## -0.28886 ``` --- ## example ```r a.1 <- aov(traffic.risk ~ tx, data = traffic) summary(a.1) ``` ``` ## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) ## tx 1 14.8 14.800 24.4 1.38e-06 *** ## Residuals 268 162.6 0.607 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## 10 observations deleted due to missingness ``` --- ## example cont ```r mod.1 <- lm(traffic.risk ~ tx, data = traffic) anova(mod.1) ``` ``` ## Analysis of Variance Table ## ## Response: traffic.risk ## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) ## tx 1 14.80 14.7999 24.398 1.381e-06 *** ## Residuals 268 162.57 0.6066 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ``` --- ## example summary Same p-values for each test; same SS; same test! - correlation gives you an effect size `\((r)\)` and `\(df\)` - *t*-test gives you a *t* & *df* (output may give you group *M* and *s*) - ANOVA gives you an `\(F\)` (and `\(SS\)`s) - linear model (regression) gives you an equation in addition to `\(F\)` and `\(SS\)` --- ## *t*-test as regression `$$Y_i = b_{0} + b_{1}X_i + e_i$$` `$$T.risk_i = b_{0} + b_{1}TX_i + e_i$$` - Each individual has a unique Y value an X value and a residual/error term - The model only has a single `\(b_{0}\)` and `\(b_{1}\)` term. These are the regression parameters. `\(b_{0}\)` is the intercept and `\(b_{1}\)` quantifies the relationship between your model of the world and the DV. --- ## What do the estimates tell us? ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = traffic.risk ~ tx, data = traffic) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -1.65064 -0.59811 -0.02668 0.54475 2.54475 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) *## (Intercept) 2.65064 0.07637 34.707 < 2e-16 *** *## tx -0.48111 0.09740 -4.939 1.38e-06 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 0.7789 on 268 degrees of freedom ## (10 observations deleted due to missingness) ## Multiple R-squared: 0.08344, Adjusted R-squared: 0.08002 ## F-statistic: 24.4 on 1 and 268 DF, p-value: 1.381e-06 ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 3 x 2 ## tx M ## <int> <dbl> ## 1 0 2.65 ## 2 1 2.17 ## 3 NA 2.29 ``` --- ## How to interpret regression estimates - Intercept is the mean of group of variable tx that is coded 0 - Regression coefficient is the difference in means between the groups (i.e., slope) --- <!-- --> --- <!-- --> --- ## How to interpret regression estimates - Intercept `\((b_0)\)` signifies the level of Y when your model IVs (Xs) are zero - Regression `\((b_1)\)` signifies the difference for a one unit change in your X - as with last semester you have estimates (like `\(\bar{x}\)`) and standard errors, which you can then ask whether they are likely assuming a null or create a CI --- ## *t*-test as regression Regression coefficients are another way of presenting the expected means of each group, but instead of `\(M_1\)` and `\(M_2\)`, we're given `\(M_1\)` and `\(\Delta\)` or the difference. Now let's compare the inferential test of the two. ??? Matrix algebra for independent samples t-test `$$\large (T'T)^{-1}T'X = (b)$$` Matrix algebra for linear regression `$$\large (\mathbf{X'X})^{-1} \mathbf{X'y}=\mathbf{b}$$` --- ```r summary(mod.1) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = traffic.risk ~ tx, data = traffic) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -1.65064 -0.59811 -0.02668 0.54475 2.54475 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 2.65064 0.07637 34.707 < 2e-16 *** *## tx -0.48111 0.09740 -4.939 1.38e-06 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 0.7789 on 268 degrees of freedom ## (10 observations deleted due to missingness) ## Multiple R-squared: 0.08344, Adjusted R-squared: 0.08002 *## F-statistic: 24.4 on 1 and 268 DF, p-value: 1.381e-06 ``` --- ```r t.test(traffic.risk ~ tx, data = traffic) ``` ``` ## ## Welch Two Sample t-test ## ## data: traffic.risk by tx *## t = 4.9088, df = 214.41, p-value = 1.814e-06 ## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0 ## 95 percent confidence interval: ## 0.2879201 0.6742914 ## sample estimates: ## mean in group 0 mean in group 1 ## 2.650641 2.169535 ``` --- ## Statistical Inference The *p*-values for the two tests are the same, because they are the same test. The probability distribution may differ, however. - *t*-test uses a *t*-distribution - regression uses an *F*-distribution for the omnibus test - regression uses a *t*-distribution for the test of the coefficients In the case of a single binary predictor, the *t*-statistic for the *t*-test will be identical to the *t*-statistic of the regression coefficient test. The *F*-statistic of the omnibus test will be the *t*-statistic squared: `\(F = t^2\)` --- ```r library(here) expertise = read.csv(here("data/expertise.csv")) cor.test(expertise$self_perceived_knowledge, expertise$overclaiming_proportion, use = "pairwise") ``` ``` ## ## Pearson's product-moment correlation ## ## data: expertise$self_perceived_knowledge and expertise$overclaiming_proportion *## t = 7.762, df = 200, p-value = 4.225e-13 ## alternative hypothesis: true correlation is not equal to 0 ## 95 percent confidence interval: ## 0.3675104 0.5806336 ## sample estimates: ## cor ## 0.4811502 ``` --- ```r mod.2 = lm(overclaiming_proportion ~ self_perceived_knowledge, data = expertise) ``` ```r summary(mod.2) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = overclaiming_proportion ~ self_perceived_knowledge, ## data = expertise) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -0.50551 -0.15610 0.00662 0.12167 0.54215 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) -0.11406 0.05624 -2.028 0.0439 * *## self_perceived_knowledge 0.09532 0.01228 7.762 4.22e-13 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 0.2041 on 200 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.2315, Adjusted R-squared: 0.2277 *## F-statistic: 60.25 on 1 and 200 DF, p-value: 4.225e-13 ``` --- ```r mod.3 = lm(self_perceived_knowledge ~ overclaiming_proportion, data = expertise) ``` ```r summary(mod.3) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = self_perceived_knowledge ~ overclaiming_proportion, ## data = expertise) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -2.8150 -0.6761 0.0103 0.7305 3.1850 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 3.6801 0.1206 30.515 < 2e-16 *** *## overclaiming_proportion 2.4288 0.3129 7.762 4.22e-13 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 1.03 on 200 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.2315, Adjusted R-squared: 0.2277 *## F-statistic: 60.25 on 1 and 200 DF, p-value: 4.225e-13 ``` --- Regression models provide all the same information as the *t*-test or correlation. But they provide additional information. Regression omnibus test are the same as *t*- or *r*-tests, even the same as ANOVAs. But the coefficient tests give you additional information, like intercepts, and make it easier to calculate predicted values and to assess relative fit. --- ## Predictions - predictions `\(\hat{Y}\)` are of the form of `\(E(Y|X)\)` - They are created by simply plugging a persons X's into the created model - If you have b's and have X's you can create a prediction `\(\large \hat{Y}_{i} = 2.6506410 + -0.4811057X_{i}\)` ```r mod.1 <- lm(traffic.risk ~ tx, data = traffic) summary(mod.1) ``` ``` ... ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 2.65064 0.07637 34.707 < 2e-16 *** ## tx -0.48111 0.09740 -4.939 1.38e-06 *** ## --- ... ``` --- ## Predictions - We want our predictions to be close to our actual data for each person `\((Y_{i})\)` - The difference between the actual data and our our prediction `\((Y_{i} - \hat{Y}_{i} = e)\)` is the residual, how far we are "off". This tells us how good our fit is. - You can have the same estimates for two models but completely different fit. --- ## Which one has better fit? <!-- --> --- ## Calculating predicted values `$$\hat{Y}_{i} = b_{0} + b_{1}X_{i}$$` `$$Y_{i} = b_{0} + b_{1}X_{i} +e_{i}$$` `$$Y_{i} - \hat{Y}_{i} = e$$` - can you plug in numbers and calculate city 3's predicted and residual scores without explicitly asking for lm object residuals and fitted values? ```r traffic[3, ] ``` ``` ## id tx traffic.risk ## 3 3 1 3.285714 ``` --- ## Statistical Inference - In making predictions, we have to compare our prediction to some alternative prediction to see if we are doing well or not. - What is our best guess (i.e., prediction) if we didn't collect any data? `$$\hat{Y} = \bar{Y}$$` - Regression can be thought of as: is `\(E(Y|X)\)` better than `\(E(Y)\)`? - To the extent that we can generate different predicted values of Y based on the values of the predictors, our model is doing well. Said differently, the closer our model is to the "actual" data generating model, our guesses `\((\hat{Y})\)` will be closer to our actual data `\((Y)\)` --- ## Partitioning variation `$$\sum (Y - \bar{Y})^2 = \sum (\hat{Y} -\bar{Y})^2 + \sum(Y - \hat{Y})^2$$` - SS total = SS between + SS within - SS total = SS regression + SS residual (or error) Technically, we haven't gotten to ANOVA yet, but you can run and interpret an ANOVA with no problems given what we've talked about already. --- ```r set.seed(0214) traffic$new_tx = sample(c("1","2","3"), size = nrow(traffic), replace = T) a.2 = aov(traffic.risk ~ new_tx, data = traffic) summary(a.2) ``` ``` ## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) ## new_tx 2 1.74 0.8697 1.321 0.269 ## Residuals 269 177.11 0.6584 ## 8 observations deleted due to missingness ``` --- ## summary The general linear model is a way of mathematically building a theoretical model and testing it with data. GLMs assume the relationship between your IVs and DV is linear - *t*-tests, ANOVAs, even `\(\chi^2\)` tests are special cases of the general linear model. The benefit to looking at these tests through the perspective of a linear model is that it provides us with all the information of those tests and more! Plus it provides a more systematic way at 1) building and testing your theoretical model and 2) comparing between alternative theoretical models You can get 1) estimates and 2) fit statistics from the model. Both are important. --- .pull-left[ <blockquote class="twitter-tweet"><p lang="en" dir="ltr">I made this meme for our stats class last week and I thought you might like to see it. <a href="https://t.co/ecnfsXHvey">pic.twitter.com/ecnfsXHvey</a></p>— Stuart Ritchie (@StuartJRitchie) <a href="https://twitter.com/StuartJRitchie/status/1188423700795801601?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">October 27, 2019</a></blockquote> <script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script> ] .pull-right[  ] --- class: inverse ## Next time Part- and partial correlations